Find, access, read, translate and understand science

on 22 September 2018

Science is a rich and exciting discipline that is often misunderstood, usually because of its media coverage. I have discussed the concept of neurofeedback extensively here, explaining its definition, its mechanism of action and possible therapeutic targets. I demystified the solutions that claimed to be it, but are not. I have allowed myself a lot of criticism, repeating over and over again: do not trust, ask for proof.

And in all honesty, in terms of neurofeedback, I didn't bring you any. It will be time to bring some, it will be the subject of the next article. What I want to explain to you here is how you will be able to verify the scientific evidence I will provide in the future. Do not trust and rely on evidence: it is being able to go back to the source of a popularization text, to check if the popularizer is not bullshitting you.

To do this, you have to start with a few things in mind.

Just a point of clarification.

In my articles, I use bold or italics to highlight important things. The indigo texts, are links, redirecting you to the source of my affirmations. Remember to click on it if you want more information. The article aims to give you the basics; the associated links, to go further.

A "book" is not scientific evidence. In a bookstore, you can find books (no kidding) written in French* by "specialists" or "experts". They are either self-proclaimed or by watching them on TV, we end up thinking that they have expertise. A book sold to the general public, in its very essence, can only be scientific popularization, which can therefore be either well done or - and this is often the rule - poorly done and aim only at self-promotion of its author who very often has something to sell you. The typical case is all these "coaches" who write books to support their opinion rather than providing you with evidence.... and when you notice a false speech, these people do not respond with scientific studies... but with general public books that go in their direction. It is therefore a closed circle that is not based on any evidence. We also have the case of former scientists recruited by the media, who have not produced anything scientifically for decades, but continue to write books on their theory... and very often, science has since evolved, while their discourse.... no.

So, if you read a book, check to see if the author cites scientific sources. I have a shovel of a book on the NeurOptimal (whose people practicing this technique gave me the references to certify that the technique worked)..... but it is 200 pages of testimonies, anecdotes of practitioner.... with 0 scientific source. So it's not evidence. Even if it's 200 pages long.

There are real scientific books (like those of the AAPB) but they are in English*. Otherwise, you have the reviews, I talk about it in point 6. This is really science taking on a new dimension.

* As a francophone, if a text is not in English, we know that it is not science at first hand. As an anglophone, you do not have this element that allows you to quickly discriminate between science and popularization.

A testimony is not evidence

In clinical science, researchers are subject to constraints other than those of laboratory researchers. In my past research (using the mouse), I couldn't rely on testimonies, so I had no problems. Seriously, have you ever seen a mouse talk ? Our work is therefore to create experimental protocols that will ask one - and only one - question to our mouse.

On the other hand, in a clinic, you can ask someone: Are you anxious? The person will answer "yes" or "no" or "maybe", but this will depend on their perception of themselves and can in no way be a good marker of anxiety. Actually, most of you are unaware of the scientific definition of anxiety. So, asking yourself if you're anxious is already biased. A questionnaire, with targeted questions, could then be considered. It's very common in clinical science, but it's not yet perfect, because it's a testimony. For example, we could want to associate this with a blood test to see if certain markers (serotonin, cortisol, catecholamine,...) are present at abnormal levels.

We move here from testimony that is unverifiable to biological data that are measurable, comparable and statistically analyzable. That's what science is all about: busting your head to find repeatable, quantifiable and comparable measurements between individuals.

Not everything in the questionnaires is good to throw away, of course. But alone, they are not enough. That is why, when a clinical study is based solely on questionnaires, I remain cautious. In Neurofeedback, combining the clinical interview with an EEGq analysis (quantitative electroencephalogram) makes it possible to add a measure of brain activity to the patient's testimony, which is then compared to others, via databases.

Beware of general media that talk about science science

Science is precise, square and let's be honest, it doesn't make you dream (no unicorns or mystical powers in our community). As a result, when the media deal with science, it is very simplified, generalized, extrapolated and often, it becomes false (like the diamond rains on Neptune, eh).

If a testimony is not evidence: a scientific study is not evidence either. Well, not immediately after its publication. So already, an article for the general public that talks about "a study released today has shown that", well, in fact, no. The study may have great results, it may even be quite correct: but only replication by other teams will ensure that the first one is validated (*). When I published my article in 2015 on my mouse, it took almost 2 years - that other studies validated my experiments - to tell me "wow, I didn't say anything stupid". Even in good faith, there may be biases that the researcher has not noticed that could make the study completely false. It's unpleasant, it happens. Therefore, a single study is not evidence until it has been replicated by others.

(*) In reality, republishing an existing result is almost impossible in science, it is not selling. What may have been published in its entirety will later be used as a small control experiment at the beginning of another paper. Or, there will be a small discreet sentence saying "we have experienced..... again and agree with them". Sometimes, the person who takes over the project in the laboratory (precariousness in science, eh), will repeat some of the experimentations of his predecessor to be quite sure of the result. It is more often when a result cannot be replicated that other researchers will be able to publish on it. Proving that we are wrong is science. Under no circumstances is it proven that something is true.

This is where we talk about meta-analyses. The meta-analysis compiles several studies on the same subject, in order to obtain an even more solid result(*). For example, in my field, it was the meta-analysis of Cotton and his colleagues that made it possible to clarify once and for all whether patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy had an alteration in their intellectual quotient (IQ). Basically, to self-quote, it looks like in a scientific context:

In their meta-analysis (1,146 patients from 32 studies conducted between 1960 and 1999), Cotton et al (2001) estimated the average patient IQ at 80.2 (significantly different from 100) with a minimum of 14 and a maximum of 134. 34.8% have an IQ below 70, and 28% have an IQ below 50. It will also conclude on an old debate: do patients have a lower verbal IQ than performance IQ? Cotton provide this answer: the verbal IQ is indeed 5 points lower than the performance IQ, but given its meta-analysis, this difference is not clinically significant..

(*) In this case, the IQ test is one of more than a dozen experiments that each study will include. This is rarely the main subject of the studies compiled by Cotton. The interest of meta-analyses is to select a parameter (here, the IQ) and extract it from many studies, which deal at the base, with another subject.

Meta-analysis therefore takes articles from 1960 to 1999: imagine if the media had to wait 39 years to talk about science! No, they talk about it right away (often before the rest of the scientific community has access to it, in fact...) to make the announcement effect work, at the risk of bullshitting. That's how we saw misconceptions that now have a hard skin coming in: the anti-vaccine movement, the memory of water to explain homeopathy, or the fact that GMOs are toxic....

The media, they are there to make money/click, so if you are looking for (quality) information, especially in science, avoid them (contradictory example: this article in Le Monde on homeopathy, doped with meta-analyses)

One exercise I regularly do in front of the news is: how much information is there in a report?

A testimony is not information, a person's feeling is not information, a micro-trottoir is not information, an expert opinion is not information. A scientific study is the beginning of information. A meta-analysis is information. You will quickly realize that on 30 or 40 minutes of the newspaper, you will learn 1 or 2 pieces of information drowned in a hundred other things that are only there to furnish and flatter your emotions.... (more information in this Horizon Gull video).

Where can I find scientific articles?

In Science, my favorite database is Pubmed. You type a few keywords and you will get a list of articles that deal with the issue.

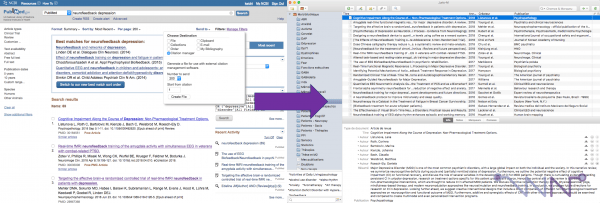

In the context of neurofeedback, PubMed lists 1,371 articles. On the right we see that the number of articles on this subject increases over the years. This does not necessarily mean that scientists are more interested in it, but more and more articles are published each year, in general, in all fields. On the left, we can also see the possibility of sorting by type (clinical trial, literature review,...), by species (human, rat, mouse,...) or by date.

The page of an article always follows the same pattern:

- at the top, the name of the journal where the article is published and the year ;

- below, the title and the list of authors. Generally, the first is the main experimenter and the last is his leader (who established the protocol / found the funding) ;

- then a summary (abstract) of the article ;

- and in the right column, you will find either a link to the full article on the publisher's website (here Frontiers) - which may be charged - and sometimes other buttons, such as here, a link to the full article, directly in Pubmed.

In France and in science, it is important to understand that:

- the researcher is paid by an organization (company or French state) ;

- the researcher manages to find funding for his research (equipment, laboratory animals,...) and pay the salaries of his students (doctoral students, masters,...) ;

- the researcher pays a publisher for the article to be published in the journal (after peer review, scientific quality is required, eh... -peers are scientists who do this on a voluntary basis at the request of publishers-) ;

- the researcher may or may not pay for the article to be available free of charge ;

- the researcher pays (or the University, or the Company) to access the scientific articles.

The extreme case is for example:

- the researcher is a public employee, therefore paid with your taxes ;

- the researcher can have funding from associations such as the Telethon, so pay for his material / students with your donations ;

- the researcher will pay a publisher with your donations to see his work - which you have funded - published ;

- the University will pay the publisher (therefore, with your taxes) for other researchers to have access to the journal where the article was published ;

- ... and you, if you want the article, you have to pay the publisher directly.

A great world, this world of scientific research, for the common good and the free exchange of knowledge.

It is a business that more and more of us are denouncing. In March 2018, my University (Paris-Sud XI) sent a message to everyone that the fees for access to some journals were too high, so we would lose access. It's still sad when you consider that the publisher only does layout and sells his access several million each year......

How to access scientific articles ?

If the article is freely available, we have already discussed the link in Pubmed to access it..

If, on the other hand, it is not free, four solutions:

- contact the researcher directly to request a copy of the article. A researcher should normally never refuse this. For a few years now, we have even had a specialized social network (ResearchGate) where we exchange articles with each other (we do other things too);

- use your University's access to the journal, which requires a university and an attachment laboratory to have the codes;

- ask nicely on Twitter, with the hashtag #ICanHazPDF ;

- or, and this is completely illegal, go through the Sci-Hub.tw website (Twitter: @Sci_Hub).

While we are all more or less familiar with illegal download platforms, Sci-Hub is its counterpart for scientific articles. To learn more, you can visit the Wikipedia page which is very well done. For the anecdote, many academics go through Sci-Hub, rather than through their laboratory accesses because it is.... easier to use. Not everything is available, but Sci-Hub can be of great help.

Other platforms exist (some of which are cited on the Sci-Hub Wikipedia page), but Sci-Hub remains the major (it is estimated that 95% of the scientific literature available on it). It's illegal, so I can't advise you to use it. After that, I can't forbid you to do it either, can I....

Beyond Sci-Hub, other cases have been published about the scientific literature. If you are interested in the subject, a documentary called "The Internet's Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz" is available for free on Amara, a collaborative subtitle platform. If you don't know Aaron Swartz, here he is in a few words:

- at the age of 12 (in 1998), he created a precursor to Wikipedia ;

- at the age of 14, he participated in the creation of the RSS standard, which is still widely used ;

- at 15 years old, he contributed to the creation of the Creative Commons license, an alternative to Copyright, widely used nowadays ;

- at 19, he contributed to the creation of the Reddit website (the eighth most visited website in the world, and the fourth in the United States) ;

- he is also a contributor to the W3C standard (for website creation) and works with J. Gruber to develop the Markdown language used by most journalists today ;

- and a lot of other things about the few years he still has to live....

On January 11, 2013, Aaron Swartz (26 years old) hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment. His federal trial in connection with the electronic fraud charges was scheduled to begin the following month. If convicted, he was liable to imprisonment for up to 35 years and a fine of up to $1 million.

This "electronic fraud" being only a small script allowing to download all the scientific articles of the publisher JSTOR (via legal access from his university, huh, but automatic scripts were very new at that time)....

That's why, today, I am a little bit of an advocate for the free circulation of scientific articles.....

Translate scientific articles

(you don't need it, you already speak English ^^)

Once the article is in hand, the most difficult thing is to read it.

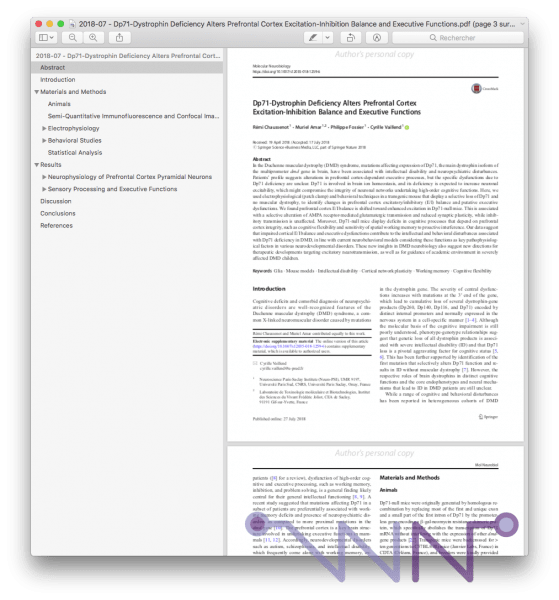

In the philosophy, all the articles are built in the same way :

- a summary (abstract, always open access) that shows what the article is about and what the conclusions are ;

- an introduction to set the context of the study and why it is interesting ;

- the materials and methods used to enable other researchers to replicate the study ;

- a results section with graphs and statistics of researchers' findings ;

- a discussion part that interprets the results and compares them with other studies ;

- a conclusion part that puts the results in perspective and, if necessary, what remains to be done ;

- a "conflict of interest" part (promised!) ;

- and a bibliography of the studies cited in the article for the reader to read for more information.

For a non-researcher, reading the introduction, discussion and conclusion is generally sufficient. The introduction will bring you some culture on the subject, the discussion will explain the results of the study and the conclusion will allow you to see what the researchers think of their study, since it is usually there, where you stick a "attention, it's results to check" or "you should also do this and that to be sure" (that in general, the media completely ignore.... HEH ......).

If you do not speak French (or German, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Polish), I strongly recommend DeepL.com, which is an automatic translator powered by artificial intelligence. It's not perfect, but frankly, it does the job pretty well. Nothing prevents you from using Wordreference or Linguee to refine the translation later on. Moreover, Linguee is the basis of DeepL and that's what makes this translator the best at the moment.

On a personal level, I use DeepL to translate the articles in this blog into English. It is not necessarily a quality English output, but it is understandable and the message that must be conveyed is getting through (you tell me). Well, I still spend a few hours correcting it on the biggest mistakes, but it works pretty well, as long as the source text is correctly written (spelling and syntax). I know that friends use it to make a first translation draft, because it is often easier to rework a text than to write it from a blank page.

Starting in science: reviews

I mentioned earlier, PubMed offers you the possibility to sort by document type and one of the filters allows you to display only reviews.

A review is written by a researcher, with the aim of taking stock of the state of knowledge on a specific subject. They are of various qualities, for these reasons :

- some researchers write reviews to increase their number of publications (which act as CVs, as mentioned here) and only copy/paste article summaries (this is apparent when you go to see the articles cited) ;

- some researchers write reviews to cite only their work (which increases their h-index, a measure of a researcher's supposed quality, it can be deduced in the end bibliography);

- some researchers write reviews to influence the scientific and media community (and do cherry-picking).

But we also have researchers who do their work very well, brilliantly synthesizing several hundred articles in a document of about ten pages, which makes it possible to begin to approach a subject with a clearer view of the current landscape. It is also the right place to give your opinion or make hypothesis. Writing a good review is the possibility of being published in a very good journal and perhaps the highlight of a scientific career (and it only takes time and a computer, it is inexpensive to produce).

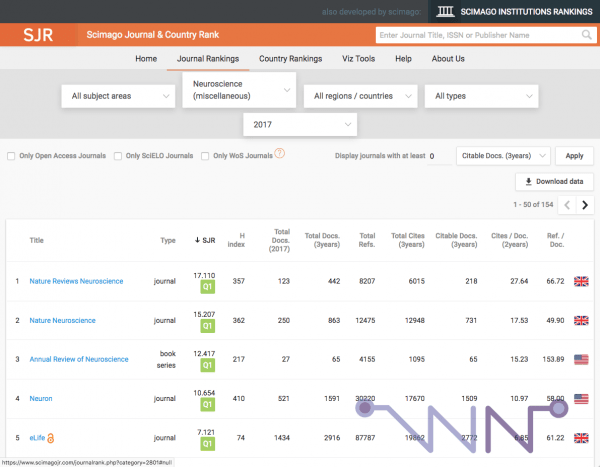

So certainly, you have to be critical, you can look at the impact factor of the journal in which the article is published, to see if this journal is reputable or not. It is by looking at this kind of table, that I took the liberty of saying that the only studies about NeurOptimal, published in journal with impact factors below 1, were probably bad. For each discipline, the values change, so it is impossible to give a general instruction for all disciplines.

Bonus : Bibliography managers

Bibliography managers are very useful for generating on-the-fly bibliographies of articles written by scientists. Not all researchers use them, some will store everything in folders and do it manually. But, it's still convenient, especially since PubMed offers the possibility to import all the articles of a search, directly in the manager.

On a personal level, I use Juris-M which is a version derived from Zotero. Others exist (see this Wikipedia page) and sometimes do much more than my Juris-M which is very austere and impractical. But I'm not a very big fan of these softwares and he was the only one who interfaced with Scrivener, my writing project management software that I love so much it helped me to write my thesis (it is paying, but will get value for your money -no I'm not sponsored by Scrivener-).

For the next article, I therefore retrieved in Juris-M all the articles that deal with a specific subject from Pubmed. Having access to the summary directly in Juris-M, I will be able to make a first selection, to see the most interesting ones. Then, with a double click, I can go to the article on the publisher's website (if it's not paid for), or give the address of this page to Sci-Hub for... you know what, now.

Conclusion

At the end of this post, you should therefore be able to look for a scientific article on Pubmed and understand its structure.

So when you are on a popularization article, if you have any doubts about the veracity of the information, look for the link to the original scientific publication and read it (usually a small "Source" link at the bottom). Quite often, you will see that between what the journalist tells you and what the researchers have written in their publication, there is a whole world.....

Concerning the diamond rain of LCI: the journalist does not even bother to give a link to the scientific study (which I found thanks to a search engine) and given the explanation of the publication made by Astronogeek, LCI for the scientific information: it is to be avoided. It is now up to you to identify the journalists who cite their sources and who make popularization in accordance with the original publication, it will make you a big selection in your reading....

To go further, I recommend these Youtube channels to sharpen your critical mind (sorry, in Franch) :

Did you like this article? Then support the blog and share it with your friends by clicking on the buttons* below :

Article url :

http://en.chaussenot.net/trouver-acceder-lire-traduire-et-comprendre-la-science

* These sharing buttons are respectful of your privacy and avoid tracking by social networks.